My Tank Park Salute

Family, running away - and coming back again.

Ever since our office moved to a site by one of Belfast’s peace walls, each walk I take to the local garage/Spar/Post Office takes me past the site of what I’m calling (and I believe it’s a legit term from psychogeography - I don’t think I’ve made it up) a ‘ghost street’; a street that once was there and isn’t any longer. This one has particular resonance for me and its a resonance that keeps bumping round my head, given how often I take that walk, and that’s because the ghost street in question is the one where my grandparents lived and my Dad grew up.

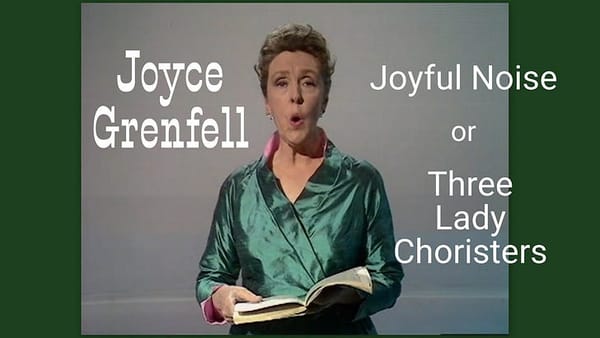

I’m not quite sure the phrase “now, you keep up with the music now. D’you hear me?’ was meant to sound quite so much like a threat, but in Granda’s particular version of Belfast vernacular, and with a voice gravelly from years of chain-smoking, it definitely carried an air of menace that seemed to jar a bit with the exhortation. It was a phrase I heard at the end of every phone call with him, because he was so very, very proud of the fact that I was musical. I can still remember, with the deep mortification that’s especially potent when you’re a teenager, being introduced in every local shop from Tesco to the butcher as, ‘my granddaughter. Isn’t she a lovely big girl? [eeesh. That line stung particularly for someone who was always tall for her age and suitably self-conscious about it] She’s very good at the music, you know’. Always ‘the music’. I was never sure why it had a definite article. He had the same pride with my younger brother, which led to an incident that has become the stuff of family legend; possibly in more families than just ours, given how many folk witnessed it. In his last year at primary school, my brother got one of the leading roles in his school panto. Despite the fact that a WWII injury had left Granda with impaired hearing, which meant he was only ever going to hear about a quarter of what was happening on stage, he insisted on coming to watch the show. My Mum had a meeting before it started, in a church next door to the primary school. Interaction with Granda before the curtain went up went as follows, conducted on Granda’s side at a volume level that said ‘well, I know I can’t hear you, so I’m going to assume you can’t hear me either’…

Thanks for reading What Happens with Music! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Granda: Where’s that friggin’ Mother of yours?

Me [desperately trying to project without raising my voice]: She’s at a meeting in the church next door, Granda. She’ll be in just before it starts.

Granda: Huh! Friggin’ Daphne. She’s always late.

Ten to fifteen minutes pass. The school choir and band start to file on stage and on cue, Mum appears.

Granda: There she is now! Friggin’ Daphne, late as usual. [to me] Will I do the fingers to her? [gesturing] Oi Daphers, up yours!!!

Me: …

Looking through the eyes of my teenage self, I can still vividly feel the excruciating mortification as I saw the people around us laugh (at or with? who knows), the stunned look on the face of the friend of my brother’s that we’d brought with us to the performance and the horrified solidarity of my Aunt, who sat on my Granda’s other side. As an adult, this is one of my favourite stories about Granda and I will happily tell it to anyone, because it seems to sum up for me his fierce pride in us, along with his capacity to create chaos in my outwardly normal, middle-class upbringing.

It was that support, given on his own unique terms, which sent my Dad and I on a visit to him when I was about 15 and at the point in my clarinet studies when I needed to upgrade my instrument. Granda listened as I explained about the challenges of creating good tone on my plastic student clarinet as I took my higher grade exams, my aspirations to study music at university, and the fact that my tutor had got agreement for a good deal for me on a new wooden clarinet. At the end of all this, he asked the cost and simply said ‘put out your hand’. I did, he produced a roll of cash, the like of which I had never seen before, and haven’t since, and counted out the amount into my hand. It barely dented the roll that came from his pocket.

Dad and I took our leave from the house and went for a coffee, slightly giggly. After a while, Dad said ‘you do understand, having seen the amount of cash he’s carrying around, why we went to talk to him about it, don’t you? He won’t put money in the bank and that’s your inheritance. He wants you to have it, and he’d do anything to keep your music studies on track, but all it would take is for someone to clock that cash while he’s out drinking and it’ll be gone.’

Ah. Ah yes, the drinking.

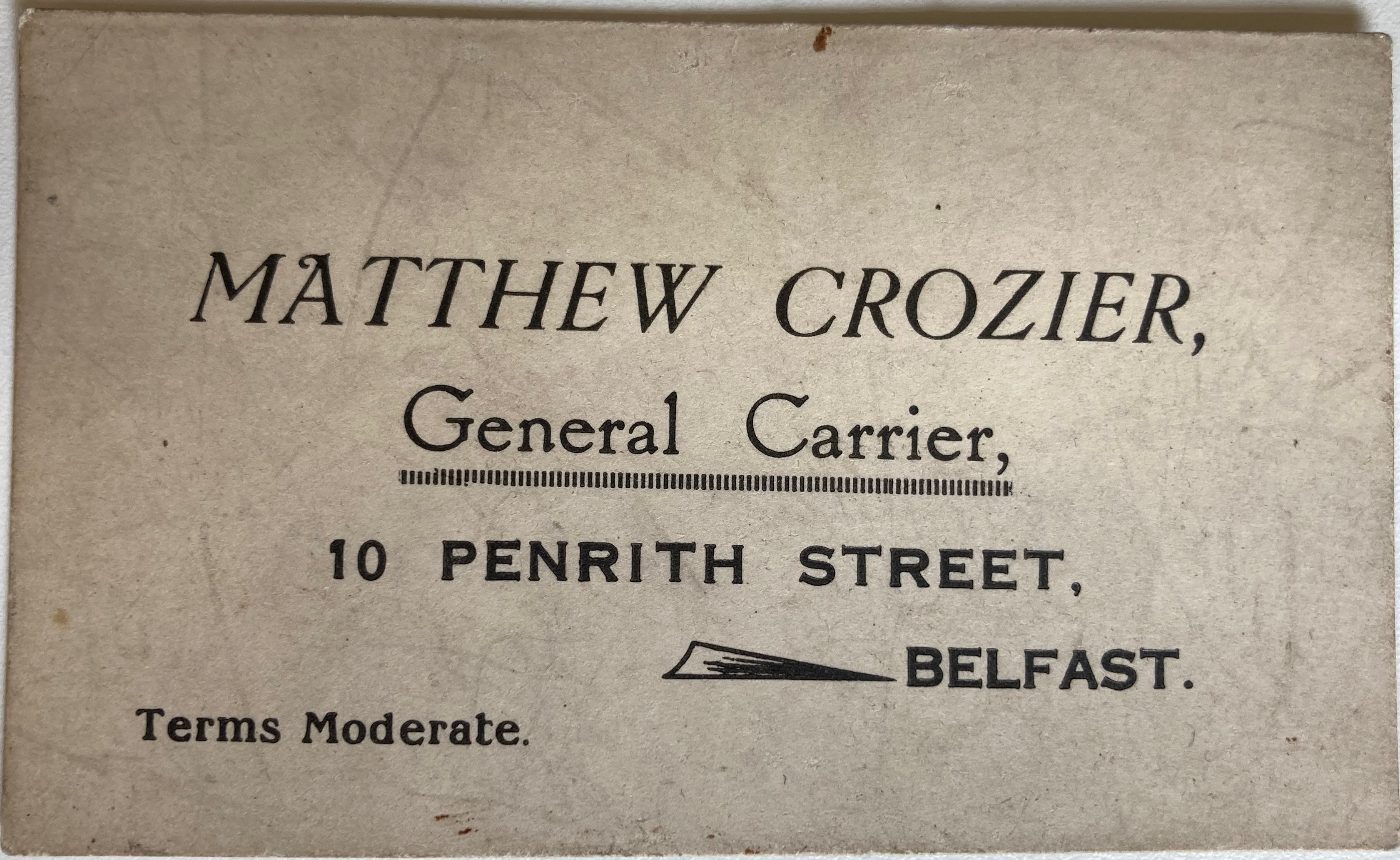

Granda lived a tough life. I know he worked for a time as a tent fitter for the circus, and I have a business card of his, bearing the ghost street address, from his time working as a ‘carrier’; tough physical labour. He kept pigs on a farm on the nearby Falls Road and buckets of scraps had to be carried up to feed them. His stint in the army in the Second World War saw him fight as a Desert Rat in North Africa and Malaysia. He came back from the war with what I am convinced we’d now diagnose as PTSD, which made for a very unhappy home. My Grandmother had her own WWII trauma, having worked as a nurse during both the Belfast Blitz and in London, so neither was in a good place to care for a child and my Dad’s upbringing was physically tough and full of neglect - in fact, he was really brought up by surrounding relatives who were appalled and ready to care where his parents weren’t. And Granda drank. We heard stories of his behaviour at his wake that were hilarious in the telling, but on reflection, I see a man fighting that PTSD and using one of the old-as-time escapes on offer, alcohol.

It has always seemed to me that Granda saw me and my brother as a chance to make amends for his behaviour and parenting when raising my Dad; we were treated equally and generously, but we were never spoiled. He was wholeheartedly unequivocal in his support of whatever we were good at and there was never any question that we were loved, we were encouraged and we were to go out and be the best versions of ourselves that we could be. Aged 17, I cried my eyes out when Granda died.

There’s a level of irony in that, at that time when Granda was doing his best to be an A* (if chaotic and sweary) elderly relative, my Dad was replicating with us the behaviour he’d seen in Granda when he was a child. Working during the Troubles scarred many NI residents and Dad was no exception, and that awful childhood was catching up on him too. Mum and I were discussing recently how sometimes, unexpected vivid memories from those years that were long forgotten pop up and surprise us; my memories of my teens are of some individual incidents, but overwhelmingly, it’s the claustrophobic, anxiety-ridden feeling of constantly living on edge that prevails. If there’s such a thing as a high-functioning alcoholic, I think that there can also be the high-functioning family of an alcoholic and while we outwardly presented - through my Mum’s extraordinary efforts to make it happen - as a bog-standard middle-class family with kids that were well-adjusted, attending school and associated activities, what I remember most from that time is walking home from school and approaching the bend in our street where I’d be able to see our drive for the first time, which was the point when I’d know whether Dad was home from work or not. If he wasn’t, I could exhale. If he was, I braced for what to expect - would he be sober? Hungover? In jolly, family man mode? Or brittle and volatile, ready to turn something innocuous into a blazing row that you could never quite work out how you’d got into?

‘Keeping up with the music’ paid off. I decided a career in music production and sound engineering lay in my future (that notion came to a very abrupt end approximately a year later, when it transpired that I was terrible at studio work) and I applied to university courses accordingly. One horribly wet November day Dad and I took the overnight ferry to Liverpool for me to attend an open day and our first stop on arriving in the city was the Beatles shop on Matthew Street so Beatles-obsessed me could invest in something suitable (a Sergeant Pepper pin badge I wore on my school blazer in a teeny tiny act of rebellion and a Twist and Shout t shirt). Despite the torrential rain, I loved Liverpool and had a ball. My dad met me at the end of the day and I remember immediately noticing he’d been drinking. He claimed that it had only been one pint of Guinness because it was so wet that he’d had to go somewhere, and part of me wanted to believe that he was telling the truth, while the other part of me wanted to ask why he didn’t go to a cafe, or a museum, or a gallery, or the cinema, or just… somewhere, anywhere other than a pub. But for once I managed not to say anything. Perhaps my excitement about Liverpool stopped me blundering into another heffalump trap that would have caused another row and soured the moment of finding out where I wanted to be next. A year later I did go to Liverpool, and by the time I left it felt like ‘the music’ that Granda had encouraged me to pursue was not just a genuine career choice, but was also giving me an escape. I felt terrible leaving my younger brother behind to weather the full force of living with an alcoholic parent, but I’d also reached the point where I needed to get out. I did run ‘to’ something, I ran to a course that would start the next phase of my life, but I also ran away.

Three weeks after I went to university my parents separated. My Dad subsequently died, aged 53, when I was 22. His funeral was in the same funeral home as Granda’s, and I can remember thinking to myself how odd it was that while I’d sobbed 5 years earlier, I couldn’t find any tears to shed at Dad’s funeral. Looking back, I don’t think it was odd at all.

You were so tall - how did you fall?

Tank Park Salute by Billy Bragg is a song I can barely listen to, because it always makes me cry. It’s a song he wrote about the death of his father and I know from reading fan forums that anyone who’s lost a parent seems to have the same reaction to it - he’s just really captured something about that particular loss that hits hard. There’s a moment in the song where he sings ‘You were so tall/How did you fall?’, which is presented simply and as a child bewildered that a parent could just… go. I can’t help but hear it with an additional inflection around a ‘fall from grace’ that seems to fit with how things went with Dad, and yet, I know exactly how he fell; a horrible combination of geography, political history and family history combined to produce toxic results and he made the same choice of coping mechanism as his father. It was just that he drank so hard, he didn’t get to make amends in the same way as Granda.

My brother has two daughters and both Dad and Granda would have adored them. They’d love the eldest’s utter joy in life, in schoolwork, in her friends, in turning cartwheels and in reading, and they’d love - Granda I think would have particularly loved - the mischievous anarchy that seems to imbue the youngest’s every action. If he’d been alive, would Dad have taken that opportunity to put things right via my nieces? It’s one of the unknowables of life, really; I’d love to hope so, because I do have happy memories of him from when I was the age that my nieces are now, but the person he became and the person who left us was beyond pulling himself back together.

Granda and Dad both have memorial trees in Roselawn, one of Belfast’s city cemeteries, up in the Castlereagh Hills. Every year around the anniversary of Dad’s death in August, I go up to ‘visit’ them both. The signage in Roselawn is thoroughly shocking, which turns what should be a moment of reflection into something altogether more enraging. Dad’s memorial tree is numbered 330 in his particular section, but you do not find it in the area marked 1 - 770, you find it in the section that starts with an arbitrary number in the thousands. I remembered that this year and as I stood at his tree, I found myself thinking ‘You idiot. You’ve missed so much and you would ADORE the girls’. I’ve been up and down with many emotions as the years have passed - grieving for a complicated parent is… well, it’s complicated - but more and more I seem to settle on a sort of impotent frustration at what he deprived himself of experiencing.

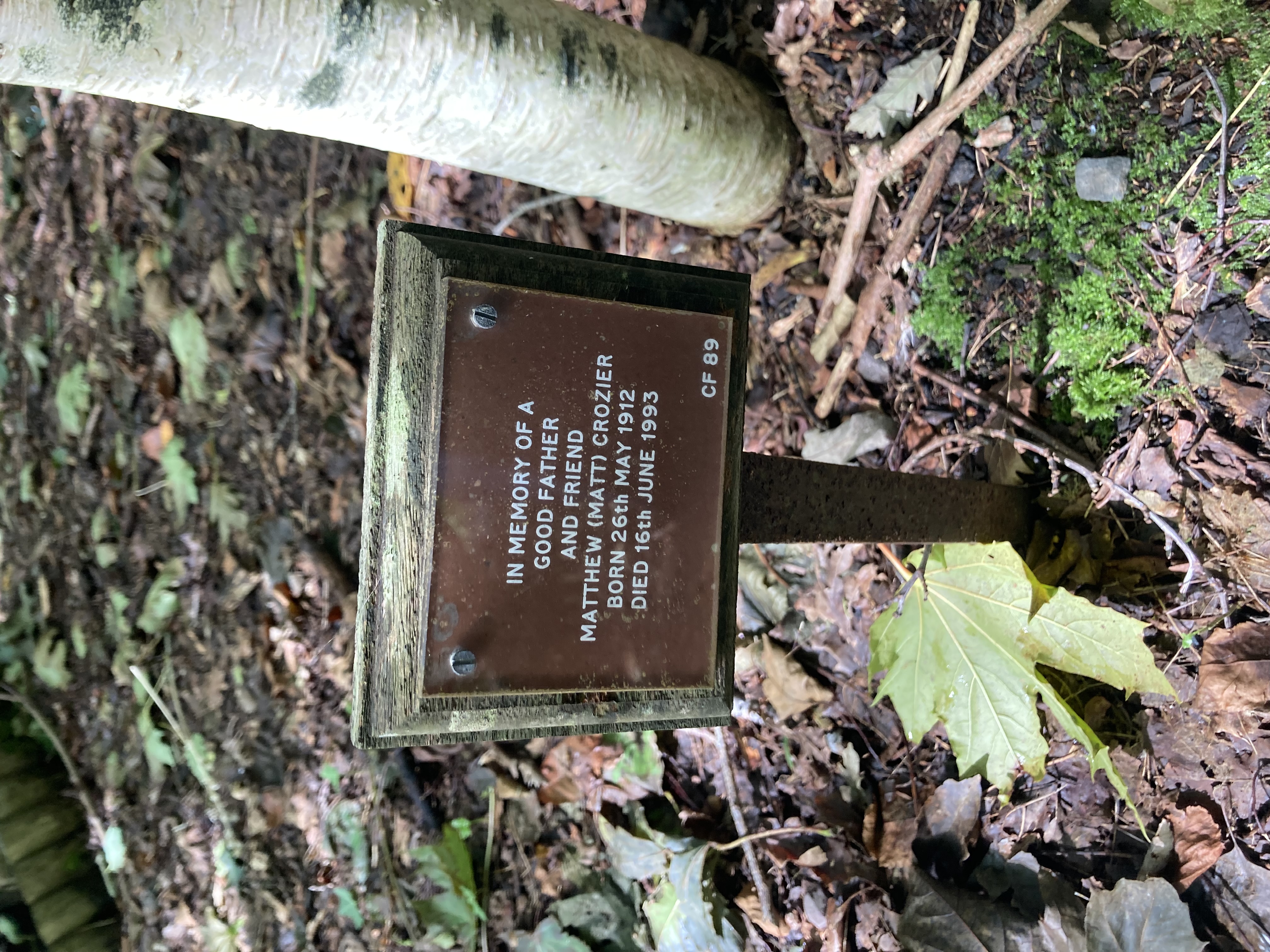

To find Granda’s tree in section CF is a whole new level of Treasure Hunt with Anneka Rice as you have to instinctively know to turn right for section R and drive past section FD in order to get there. Most years it takes me about 3 goes to get it right and I arrive at CF irritated and internally swearing, which feels fitting for a visit to Granda. This year, I got it right first go and arrived a little bewildered at my cleverness, despite my lack of Lycra jumpsuit, helicopter and directions from Wincey Willis and Kenneth Kendall. As I have done for the last couple of years, I thought ‘Granda, you always said I should keep up with the music, and I have, and it’s taken me all sorts of places. But you still wouldn’t believe that of all the places it’s taken me, it’s brought me full circle’. I think Granda would be staggered and not a little amused to think of an orchestra down the street from the family home, and no doubt he’d have found occasion to greet folk in the same way he greeted Mum in that assembly hall all those years ago, but boy, would he be proud of me and my job in ‘the music’. For me, there’s something neat, if a bit eerie, that while music let me run away, it drew me back, first to Belfast and ultimately, to where so much family history started.

I think of Dad, Granda, and their wider family (especially Dad’s Aunt Lizzy and his cousin Mina) on practically a daily basis now, as I go about my working day. The family ghosts hover around the ghost street that was their home and for the most part it’s friendly and comforting to feel them there, though it’s always tinged with a sadness that life in that place was hard and harrowing. Billy Bragg’s song is an uncomplicated mourning for a father he loved without complication, and I can’t write that. But sad, frustrated and imperfect though this is, it’s my tribute: I offer up to the Crozier ghosts on the ghost street my own Tank Park Salute.

A few years ago via social media, I discovered a charity called NACOA - the National Association for Children of Alcoholics. It’s a Bristol-based charity founded in 1990 to provide help and support for everyone affected by a parent’s drinking. They believe that every child has the right to a happy childhood and to live a creative and meaningful life but when drink is the family secret they are more likely to experience family violence, neglect and other problems in their own homes. 1 in 5 children in the UK live with a parent who drinks hazardously and yet there are no government-funded support services for children of alcoholics - so everything NACOA does is funded by donations. Because I am a middle-aged fool, I have secured a place in the Great North Run in Newcastle-upon-Tyne on Sunday 7 September 2025 and I will be using this expedition of idiocy as an opportunity to raise some funds for NACOA. I’d have bitten your hand off for support like theirs when we were living with Dad. If you’d like to contribute, you can visit my fundraising page.

Thanks for reading What Happens with Music! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.